The notes I took are sections from the Gita Guide that I find interesting. They are not from my intellect or mind.

By: Hasti Gopala dasa

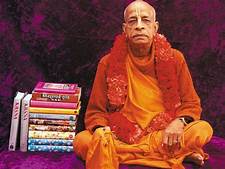

The ease and clarity with which the author expounds upon the text beckon even students unfamiliar with Indian religious tradition into a genuine understanding and appreciation of this monumental work.

Other features, such as the fifty-six color paintings illustrating the text, and informative introduction, indexes, a glossary, a guide to pronunciation of the Sanskrit, and the other appendixes, make this edition of Bhagavad-Gita a real treasure to students of this perennial classic.

The Gita has long been considered the essence of Vedic philosophy and spirituality. As the essence of the 108 Upanisads, it is sometimes referred to as Gitopanisad.

Arjuna, forgetful of his prescribed duty as a ksatriya (warrior) whose duty is to fight for a righteous cause in a holy war, decides, for personally motivated reasons, not to fight. Krsna, Who has agreed to act as the driver of Arjuna’s chariot, sees His friend and devotee in illusion and perplexity and proceeds to enlighten Arjuna regarding his immediate social duty (varna-dharma) as a warrior and, more important, his eternal duty or nature (sanatana-dharma) as an eternal spiritual entity in relationship with God. Thus the relevance and universality of Krsna’s teachings transcend the immediate historical setting of Arjuna’s battle field dilemma. Krsna speaks for the benefit of all souls who have forgotten their eternal nature, the ultimate goal of existence, and their eternal relationship with Him.

It is important to note, in this connection, that the humanlike form of Krsna visible to Arjuna on the battle field is not a material, carnal form “assumed” or “manifested” by Krsna for the world of men. According to the text, the form seen by Arjuna is Krsna’s own original form, purely spiritual and transcendental. But although Krsna is visible to all those present, only those with eyes “tinged with devotion” can understand that He Himself is the “Supreme Person,” the Godhead. The universal form (visva-rupa) revealed by Krsna to Arjuna in the eleventh chapter is not in any sense a higher manifestation of Krsna, but only a temporary display of His controlling power as eternal time (kala) in the cosmic universe.

Since religion-philosophical concepts are most often experientially based, it is increasingly evident that to gain more than stereotyped or superficial knowledge, the student or researcher must approach the subject not as a hostile critic but as a cautious sympathizer, as unhampered as possible by his own academic or personal prejudices. This is how we should approach the Gita.

Especially when dealing with Vedic spiritual philosophy, which is never theoretical but always aimed at practical transformations of consciousness and perception, we should approach with philosophical introspection. Indeed, intellectual astuteness without sincere eagerness to understand truth has always been considered, in Vedic culture, ineffectual in the realm of spiritual knowledge. The mysteries of transcendental wisdom are revealed to one who has firm faith in God and guru: “Only unto those great souls who have implicit faith in both the Lord and the spiritual master are all the imports of Vedic knowledge automatically revealed.”

In the traditional Vedic system of education, the disciple always approaches the guru in an attitude of submission and faith.

After choosing a qualified guru, he submits himself for instruction in a humble, non-arrogant way, as Arjuna does in the Gita itself: “Now I am confused about my duty and have lost all composure because of weakness. In this condition I am asking You to tell me clearly what is best for me. Now I am Your disciple, and a soul surrendered unto You. Please instruct me.” [BG 2.7] Frequently, throughout the text, Krsna reminds Arjuna that He is revealing confidential truths because of Arjuna’s faithful, non envious attitude. At the conclusion of His teachings, He instructs Arjuna further, “This confidential knowledge may not be explained to those who are not austere, or devoted, or engaged in devotional service, nor to one who is envious of Me.” [BG 18.67]

Although we ourselves may not be approaching the Gita as disciples but as critical students, if we study it in a mood of critical introspection and philosophical inquisitiveness, our experience of the Gita will be more penetrating.

Yoga involves withdrawing the mind and senses from sense objects and, through unattached action, meditation, philosophical speculation or devotion (depending on which system of yoga one employs), gradually detaching oneself from the mundane world and ultimately realizing the self and his relationship with God.

Although there is some mention of Astanga-yoga (“the eightfold path”), the Gita deals primarily with three important systems of yoga; Karma-yoga (“the yoga of action”), jnana yoga (“the yoga of knowledge”) and bhakti-yoga (“the yoga of devotion”). In karma-yoga, one acts in selfless duty to the Supreme, sacrificing the fruits of one’s work to God. This purifies the actor and releases him from material entanglement. In jnana-yoga, on gradually cultivates spiritual knowledge by philosophical induction, exercising the intellect to differentiate between matter and spirit.