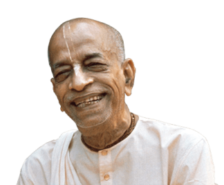

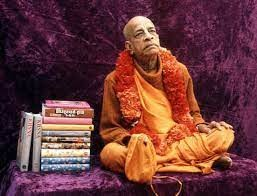

Hare Krsna. All glories to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and all Vaisanvas.

We present some quotes from “The Hare Krishna Explosion” book where Hayagriva Prabhu states that he consulted with Srila Prabhupada for editing all his books.

https://theharekrishnamovement.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/the-hare-krishna-explosion.pdf

|

CONTENTS Note Preface Part I: New York, 1966 • Visitor from Calcutta • Transcendental Invitations • Who Is Crazy? • Second Avenue Fire Sacrifice • The Hare Krishna Explosion • Back to Godhead Part II: San Francisco, 1967 • Swami in Hippieland • Flowers for Lord Jagannatha • Mad After Krishna • Soul Struck • San Francisco Rathayatra • Passage to India

theharekrishnamovement.files.wordpress.com

|

The purports are intended to bring the meaning back to Krishna,to rectify the mischief done by these rascal commentators.Factually, this is the only authorized translation. [Chapter 9, Mad After Krishna]

There are many who say that 1972 First Cantos had discrepancies. BUT WE SEE HERE THAT HAYAGRIVA PRABHU AND SRILA PRABHUPADA WORKED ON THESE AND SRILA PRABHUPADA APPROVED THE WORK.

Chapter 2, Transcendental Invitations.

The next morning, when I go alone to see the Swami, he seems to be expecting me. Directly and simply, he begins to explain that he needs help in spreading Krishna consciousness around the world. Noticing that he has been typing, I offer to type for him, and he hands me the manuscript of the First Chapter, Second Canto, of Vyasadeva’s Srimad-Bhagavatam.

“You can type this?”

“Oh yes,” I say.

He is delighted. We roll a small typewriter table out of the corner, and I begin work. His manuscript is single spaced without margins on flimsy, yellowing Indian paper. It appears that the Swami tried to squeeze every word possible onto the pages. I have to use a ruler to keep from losing my place.

The first words read: “O the king.” I naturally wonder whether “O” is the king’s name, and “the king” stands in apposition. After concluding that “O King” is intended instead, I consult the Swami.

As I retype another paragraph, I notice certain grammatical discrepancies, perhaps typical of Bengalis who learned English from British headmasters in the early 1900s. Considerable editing is required to get the text to conform with current American usage.

After pointing out a few changes, I tell the Swami that if he so desired, I could make all the proper corrections.

Thus my editorial services begin.

I type all morning in the room where he reads, translates, welcomes visitors, and “takes rest.” There is a tin footlocker, used as a desk, and a rug on which he sits and sometimes sleeps. Apart from my typewriter table, there is no other furniture. As I type, I hear him cooking in the kitchen, and can smell the butter being boiled to make ghee. I finish the chapter: twenty pages, double spaced with wide margins. The original had filled only eight pages.

“Let me know if there’s any more work,” I tell him. “I can take it back to Mott Street and type there.”

“More? Yes,” he says. “There is lots more.”

He opens the closet door and pulls out two large bundles tied with saffron cloth. Within, he shows me thousands of pages of single spaced, marginless manuscripts of literatures unknown in the Western world. I stand before them, astounded.

“It’s a lifetime of typing,” I protest.

—————————————————————————————————

Chapter 9, Mad After Krishna

Although I write on the Lord Chaitanya play through the spring days, my primary service is helping Swamiji with Bhagavad-gita. He continues translating, hurrying to complete the manuscript but still annotating each verse thoroughly in his purports. Daily, I consult him to make certain that the translation of each verse precisely coincides with the meaning he wants to relate. “Edit for force and clarity,” he tells me. “By Krishna’s grace, you are a qualified English professor. You know how grammatical mistakes will discredit us with scholars. I want them to appreciate this Bhagavad-gita as the definitive edition. All the others try to take credit away from Krishna.”

I am swamped with editing. Since much of the text is equivocal due to grammar, I find myself consulting Swamiji on nearly every verse. It seems that in Sanskrit, Hindi, and Bengali, phrase is tacked onto phrase until the original subject is lost.

No one has yet asked Swamiji the language in which he thinks. Bengali, I presume, but for all I know it may be Hindi or Sanskrit. He often says that Sanskrit is the language of the demigods, the original language, and that all other languages descend from it. Indeed, it was the very language used by Krishna when He spoke Bhagavad-gita millions of years ago to the sun god Vivasvan, and then five thousand years ago to Arjuna at Kurukshetra. All seven hundred verses sung in Sanskrit.

Swamiji sweeps away archeological and philological pronouncements with a disdainful sweep of his hand.

“What do they know? Great civilizations were existing on this earth hundreds of thousands of years ago. They are thinking that everything begins with them, with cavemen or monkeys. But in ages past, Maharaj Bharat ruled the entire world, and there were great civilizations everywhere. Who can deny that Sanskrit is the mother of languages? So-called scholars are simply concocting nonsense, proposing theories. Their business is: ‘You propose a theory, and I propose a greater theory.’ But Bhagavad-gita is not theory. It is fact. Therefore I am presenting it as it is. Not as it seems to me, but as it is spoken. Radhakrishnan says that we are not to worship the person Krishna, and Gandhi says that Kurukshetra is a symbol for this or that, but these are all opinions. Mental speculations. To expose them, we must quickly publish Bhagavad-gita As It Is. Someone has told me that the purports are very lengthy, but that is the Vaishnava tradition—constantly expanding. The purports are intended to bring the meaning back to Krishna, to rectify the mischief done by these rascal commentators. Factually, this is the only authorized translation. So I am eager to see our Bhagavad-gita published complete.”

In New York, Brahmananda continues negotiations with publishers. Swamiji consults more private printers in San Francisco. Since it is turning into such a lengthy book, it will be expensive. Swamiji also wants to include the Sanskrit Devanagari, which will cost extra. Prices are way out of our reach. We are still trying to scrape together rent for the temple and Swamiji’s apartment. In New York, it’s the same. And Kirtanananda might get kicked out of the bowling alley any day. None of us really wants to count the assets of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. Really, we have only one asset —His Divine Grace himself.

————————————————————————————-

Daily now, in the early mornings before any of us awake, Swamiji continues typing out his translation of Bhagavad-gita. Months ago, in February, he had recorded a kind of foreword, which Satsvarupa now types up as “Introduction to Geetopanishad.” Meanwhile, I continue typing the Second Canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam, keeping editorial changes at a minimum, correcting only grammatical transgressions. I also continue compiling Back To Godhead and writing essays on the nonmaterial Self and the spiritualization of energy. All the magazines sell out. The stencils, unfortunately, won’t print more than a hundred copies of each edition. We consider a printer, but prices are beyond us.

—————————————————————————————-

Swamiji continues working throughout December on his translation of Bhagavad-gita. I rarely see him work because of his schedule. He sleeps from eleven at night until about two or three in the morning. Then he gets up, and, using a dictaphone, dictates extensive commentaries on Bhagavad-gita while the great metropolis sleeps.

Citing a simile from Bhagavad-gita, he has told us that the material world is like a banyan tree with its roots above and branches below. A tree appears this way when pervertedly reflected in water. In the material world, everything is topsy-turvy; what is bad appears desirable, and what is actually desirable appears repugnant. When I see Swamiji taking rest just as most New Yorkers are indulging their senses, and getting up to render Krishna service just when they are taking rest, I’m reminded of the Bhagavad-gita verse: “What is night for all beings is the time of awakening for the self-controlled; and the time of awakening for all beings is night for the introspective sage.”

At seven, he comes down to the temple to lead morning kirtan and to lecture. Then he returns to his apartment, showers, eats a light breakfast, and reads over manuscripts, or advises us. In the afternoon, after eating prasadam, he chants some rounds and then rests for an hour, lying on his side on the rug before his footlocker.

Satsvarupa types up the manuscripts from the dictaphone tapes. Sometimes, when he can’t understand what is said, he has to consult Swamiji. The manuscript runs into hundreds of pages. Swamiji is a very prolific writer indeed.

“I wrote the introduction one night last February when I was alone,” he tells me. “I was just sitting in my apartment and had no one to talk to, and I remembered my spiritual master saying, ‘If there is only one person present, that is all right. Preach to him about Krishna. And if no one is present, you can preach to the walls.’ So I was preaching to the walls. But I had this tape recorder, and what I spoke can now be heard by you. That was the introduction to this Bhagavad-gita.”

As Swamiji begins work on the last six chapters of Bhagavad-gita, he tells me that I can now start editing it.

Swamiji sends Brahmananda out to try to interest publishers. Daily, Brahmananda draws up lists of publishers and sets out on the subway for midtown, waiting in offices for hours to see businessmen intent only on quick sales.

“There’s just no money in swamis,” one tells him. “Risky. Very risky.”

———————————————————————————————————–

Chapter 12, Passing to India

After the Rathayatra festival, Swamiji tells me that I should live at Paradisio and work full time on the final manuscript of Bhagavad-gita. In New York, Brahmananda continues to negotiate with publishers. The books must be printed at all costs. My job: prepare the manuscript nicely.

“It must be well stated in the English language,” Swamiji insists. “If there are any questions about the translations, you may ask me. Remember, edit for force and clarity.”

Daily, I try to clarify and strengthen the sentences without changing the style or meddling with the meaning, and, needless to say, this is very difficult. I soon find myself consulting Swamiji on every other verse, and occasionally he dictates an entirely different translation. The verse translations themselves are most problematical because they often differ from the word by word Sanskrit-English meanings accompanying them. What to do?

“Quit bothering him,” Kirtanananda tells me. “Whenever anyone’s in his room, he talks to the point of exhaustion.”

True. He talks sitting up. Then he leans back and talks. Then rests on one elbow. Then lies on his side, still talking, still clarifying, still praising Krishna.

At this time, he tells Haridas: “I no longer have a physical body. It is all spiritual.”

Haridas leaves his room almost in tears. “Swamiji’s more beautiful than ever,” he tells me. “Is it possible for your spiritual master to make spiritual progress?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “He says that spiritual life is always dynamic.”

“He seems to be vibrating on a much higher platform now,” Haridas insists.

“Others are saying the same,” I say. “But it could be just our perception.“

“He’s chanting more now,” Haridas insists. “Even more than at Mishra’s, more than I’ve ever heard him chant before.”

“I wouldn’t want to speculate about it,” I say.

————————————————————————————————————